How the 21st-Century School Contributes to the Mental Health Crisis — and What We Can Do to Repair It

by Alfredo Cuéllar

For DEBATEX / Special Essay

Introduction

I have dedicated more than half a century to education. During that time, I have visited hundreds of schools in different countries—mainly in the United States and Mexico—and worked with thousands of teachers, principals, supervisors, and inspectors in professional development programs that I have designed and led in universities, ministries of education, school districts, and research centers. I have created institutions, graduate programs, models of educational innovation, and school transformation initiatives that continue to influence practice in various regions.

Although this article focuses on the educational reality of the United States, many of its conclusions also apply to Mexico and many other nations. In Mexico, the so-called Nueva Escuela Mexicana still struggles to define itself, to be understood, and to be implemented without rigorous evaluations that could validate its effectiveness. Its proposal contrasts, in several ways, with the high-performance models operating in many U.S. schools.

What I present here is not a minor diagnosis. It is a major crisis—profound and structural—that affects education in the United States and has been approached with a mistaken premise: assuming that students are the problem and schools are functioning well.

This article argues, with evidence and analysis, that the opposite is true. It explains what is happening, why it is happening, what forces have shaped today’s new wounded childhood, and what solutions could help repair what has been fractured.

- A Troubled Nation: Children Are Not Well

In the United States, we face an uncomfortable and undeniable reality: childhood is deeply unwell, and a significant part of the problem lies in the institution where children spend most of their waking hours: the school.

The recent data are staggering:

- 1 in 4 seventeen-year-old boys has an A.D.H.D. diagnosis.

- One million additional children were diagnosed between 2016 and 2022.

- Autism has increased from 1 in 2,500 children in 1980 to 1 in 31 today.

- 32% of adolescents have been diagnosed with anxiety.

- More than 1 in 10 has experienced major depression.

- Anxiety begins early: the median age of onset is six years old.

These figures reveal not only an epidemiological shift but a civilizational one: childhood now exists under a regime of adult expectations that no previous generation was asked to endure.

The tragedy is that while diagnoses multiply, the nation remains trapped in an incomplete conversation that treats symptoms but avoids causes. And the main cause—silenced across decades of educational reform—is right in front of us: the radical transformation of the school environment.

- How School Became a Toxic Ecosystem for Child Development

Since the 1980s, beginning with A Nation at Risk, American education has turned into a laboratory of metrics, standards, and accountability—where schooling shifted from educating children to producing measurable outcomes through standardized testing.

The cumulative effect has been devastating:

- School stopped being a space for development and became a space for performance

Before 1980, fewer than half of children attended kindergarten; pressure was low, and academic failure did not constitute a personal catastrophe.

Today, even in preschool, 3- and 4-year-olds are expected to sit still, follow rigid instructions, and meet academic mini-objectives that contradict what developmental neuroscience tells us about early childhood. For many, this is unbearable.

- Recess, free play, and social time were drastically reduced

Only eight U.S. states currently require daily recess.

Many elementary school children have barely 20 minutes to eat, stand in line, walk to the cafeteria, and use the restroom.

- Academic pressure moved to increasingly younger ages

With Common Core (2009), reading proficiency at the end of kindergarten became standard—even though thousands of children are not neurologically ready to read at age five.

- Teachers work under structural stress

Teachers now work in conditions of permanent structural stress: stagnant salaries, rising burnout, relentless pressure for results, and evaluations that never stop. Under such conditions, the classroom ceases to be a balanced pedagogical space and becomes an emotionally contaminated one, where adult exhaustion inevitably leaks into children’s lives.

Principals are required to show continuous improvement in indicators that depend almost exclusively on how students perform on standardized tests. Results turn into statewide rankings—public scoreboards—where schools in the lower half are stigmatized, and principals and teachers face pressure, scrutiny, and unrealistic expectations to “fix” outcomes within impossible timelines.

This system forces teachers to resort to a widespread and deeply harmful practice: “teaching to the test.” That is, replacing integral education with mechanical preparation focused on how to answer correctly, which test strategies to follow, and how to maximize scores—instead of fostering critical thinking, creativity, or meaningful understanding.

The result is clear: an exhausted teaching force, emotionally fragile school climates, and instruction reduced to institutional survival.

- A school ecosystem where “being normal” is increasingly difficult

The restless child, the slow one, the shy one, the impulsive one, the distracted one—perfectly human variations—are now automatic candidates for a disorder.

As one specialist put it:

“Instead of fixing school, we decided to fix children.”

III. The New Pathologies of Modern Childhood

New clinical realities have emerged ones that did not exist before or did not exist with today’s intensity:

- Disorders associated with digital overstimulation

Screens and constant interaction → insomnia, irritability, anxiety, dopaminergic dependence.

- Anticipatory school anxiety

Children who somaticize—stomachaches, sweating, trembling—before class.

- Chronic cognitive fatigue

A product of excessive homework, fragmented schedules, and constant testing.

- Emotional regulation disorders

School teaches “control,” but not self-regulation.

- Relational disorders

Deficits in social skills caused by less free play, less authentic interaction, and more time on smartphones, computers, or tablets.

- Psychosocial disconnection

Adolescents feel school has no meaning:

80% report stress, and 70% report boredom (Yale, 2020).

- A Micropolitical Reading of the Crisis

Micropolitics teaches that every institution is a space where invisible powers circulate. School is no exception. Following foucaultian logic, these forms of power are exercised by the institution itself—and they are harming students.

Powers shaping the crisis include:

- The power of test-driven standards that define who “succeeds” and who “fails.”

- The power of diagnosis, labeling children as capable, problematic, or exceptional.

- The power of institutional stress, cascading through the entire structure and affecting principals, assistant principals, teachers, counselors, students, and families.

- The power of the success economy, turning childhood into a permanent performance race.

- The power of total visibility, where every mistake is recorded, compared, and archived.

- The power of adult surveillance, limiting autonomy and reducing exploration.

From a micropolitical standpoint, the current crisis does not arise solely from pedagogical problems but from an architecture of power that subjects children to pressures for which they are not biologically prepared. Childhood—rather than an expansive developmental period—has become a territory of compliance, measurement, and control.

- What Can We Do?

Toward an Ethical and Structural Repair

The crisis is serious, but not irreversible. There are clear and achievable paths to rebuild a healthy school environment:

- Restore play, movement, and exploration

The child’s brain is not designed for sedentary routines. Recess must be mandatory, extended, and protected. Schools that increase free-play time show improvements in behavior, learning, and emotional health.

- Reduce standardized testing and eliminate school rankings

Evaluation is necessary; punishment through data is not. Rankings create institutional stress and distort the educational mission. Schools need formative assessments, qualitative diagnostics, and improvement systems without stigmatization.

- Retrain teachers in emotional regulation and low-stress environments

A teacher’s emotional health is central to a child’s emotional health. Programs for self-care, reasonable workloads, emotional coaching, and administrative support are essential.

- Reintroduce the pedagogy of meaning

Adolescents are not disconnected due to apathy but due to lack of purpose. Schools must teach for life, not only for tests: purpose, ethics, creativity, critical thinking, and real-world problem solving.

- Rebalance the school–family relationship

Families need guidance, not surveillance, support, not judgment. Parent-education programs, respectful communication, and healthy screen-time limits are urgently needed.

- Critically review the childhood diagnostic system

Not every behavior outside the norm is a disorder. Diagnosis must be prudent, integral, and contextualized considering the school environment before labeling or medicating.

- Mandatory parent education

No reform will succeed if families remain outside the process. Schools must require parent education on child development, healthy limits, responsible screen use, emotional regulation, and school-related stress. This is not about policing families but equipping them with real tools to support their children.

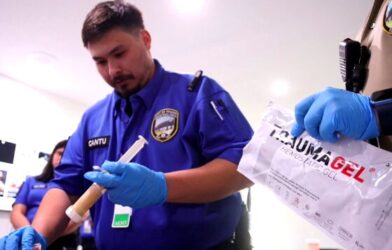

- Create mental-health clinics inside schools

Schools must have internal mental-health clinics staffed with professionals in child psychology, counseling, early-intervention strategies, and emotional support. The pandemic revealed that the traditional model—one counselor for hundreds of students—is inadequate.

If financial resources do not allow a clinic in every school, a regional system must be implemented: one mental-health clinic for every five schools, with a multidisciplinary itinerant team offering urgent care, early-intervention services, ongoing emotional assessments, and support for teachers and families.

This model—already adopted in various European and Canadian districts—reduces crises, improves school climate, detects problems early, and supports both children and families. It is, concretely, the most efficient and cost-effective long-term investment for restoring emotional well-being in schools.

- Conclusion

We are witnessing a new wounded childhood, shaped by institutional pressures implemented without neurodevelopmental understanding and without regard for the human consequences of decades of test-driven reform. The 21st-century school has placed expectations on children for which they are not ready, stripping away essential time for play, silence, rest, and meaning.

The good news is that this wound can be repaired.

It requires political will, professional ethics, and a profound rehumanization of the school environment. Children do not need more diagnoses; they need better schools—schools where development matters more than performance, where well-being is an institutional priority, and where childhood can once again be what it was meant to be: a time to grow, discover, and build a future without fear.

Micropolitics reminds us that no educational reform will succeed if it ignores the invisible forces operating inside schools. The crisis in children’s mental health did not appear by accident; it emerged from an architecture of power that imposed metrics, surveillance, pressure, and control on teachers and students—decisions made with good intentions by leaders of the time, implemented with almost no resistance.

That is why the solution cannot be merely technical; it must also be micropolitical.

Educational leaders—principals, supervisors, school boards, lawmakers—must develop a critical awareness of the power they exercise and the impact that power has on the emotional lives of children. Restoring childhood requires transforming power relations: less vertical pressure, more horizontal dialogue; less control, more autonomy; less institutional punishment, more human support.

In micropolitical terms, this means:

- creating schools where authority is not imposed through fear but through ethical legitimacy;

- building environments where well-being is a form of power—not a rhetorical ornament;

- and forming educational communities where children are not objects of control but subjects of dignity.

Micropolitics offers an indispensable insight: without transforming the power dynamics that are harming schools, no intervention will endure.

Rehumanizing childhood requires rehumanizing the exercise of power.

Alfredo Cuéllar: Educator with more than half a century of experience, creator of Micropolitics, and trainer of school leaders, teachers, and educational administrators in several countries. He has taught in prestigious universities, including Harvard, and is currently completing the final edition of his foundational work: Micropolitics: The Exercise of Power, soon to be published on Amazon Books. Contact: alfredocuellar@me.com